Pamela Vandyke Price had been replaced as The Times’ wine writer by Jane MacQuitty in the early 1980s. The transition was contested; the merits of a youthful approach to wine writing were impugned by the elder party; and the controversy spilled, like an overfull glass of Côtes du Rhône, onto the pages of this magazine. I wrote in support of youth – and Jane, now a doyenne herself.

Taste rare and exceptional wines at the Cellar Collection at Decanter Fine Wine Encounter London. Limited tickets available – book now

The wine world has never seen change to match the last half-century. The 1975 timing of founders Colin Parnell and his abrasive and often inebriated editor Tony Lord (who noisily defended South Africa’s apartheid regime to me on our first meeting) looked spectacularly poor. Bordeaux prices had collapsed, and the region was mired in multiple scandals; Herman Cruse IV, scion of one of the region’s most distinguished négociant families, had committed suicide by jumping into the Gironde the year before. European agriculture was in thrall to the ‘convenience’ of herbicides and pesticides: French vineyards, when I first visited them, were uniformly brown and bare. The quality of the Burgundies I bought was wretched, possibly inauthentic. The UK lay outside what was then known as the EEC; the label of my first Châteauneuf (I collected labels) said ‘Grand Vin de Bourgogne’ under the appellation name.

The wine-producing nations of Central and Eastern Europe were mired in Soviet Bloc productivism (the drive to maximise production); Georgia itself was buried inside the Soviet Union. Dictatorship in Portugal had only just ended, as had the rule of Greece’s military junta; Spain was still a dictatorship. Miguel Torres had yet to go to Chile (whose own military dictatorship had just begun). The first modern vines had only just been planted in Marlborough; Oregon and Washington were in their infancy; Australia was sending Kanga Rouge to the UK. Chinese wine? Forget it: the Cultural Revolution was just coming to an end, under the control of the Gang of Four; Mao was still alive.

And then… everything began to change. From the 50-year perspective, Parnell and Lord’s timing was – luckily – perfect: the wine world was about to blossom like a cherry tree. Now we can eat the cherries: magnificent wines, far finer than anything I tasted back in the 1970s, from multiple sources. All of us can name dozens of favourites. Not every development is welcome – the 21st-century rebranding of fine wines as luxury goods, with prices laughably beyond the means of most, is regrettable. Though perhaps inevitable.

What happened? Three things. Political change was the most significant: democratisation (notably the collapse of the Soviet Union and the ending of military dictatorships and apartheid), economic reforms and globalisation have enabled the endeavour and commercial freedom that wine creation needs in order to flourish; essential agricultural changes accompanied this. The rise of a consuming wine culture on a global scale was the second, aided by wine media (Decanter has played a modest part). And the third? It’s a phrase first employed by US scientist Wallace Broecker in a paper in 1975: global warming. Most wine-growers have enjoyed life in the Goldilocks zone so far: wine has been a beneficiary of multiple ripe vintages in regions where these were formerly a rarity, while places once too cool for fine wine (like England, Ontario, Central Otago, the Adelaide Hills, Gualltallary) are so no longer.

The next 50 years? That’s up to us. We can elect populists, erect trade barriers and wreck free trade. We can attempt to freeze the social fabric of our societies. We can take refuge in the comfortable stupidity that ignores climate change, and spurn the massive transition efforts that are now essential. And we can watch the extraordinary wine-world advances of the last half-century endangered, perhaps destroyed. Or not.

In my glass this month

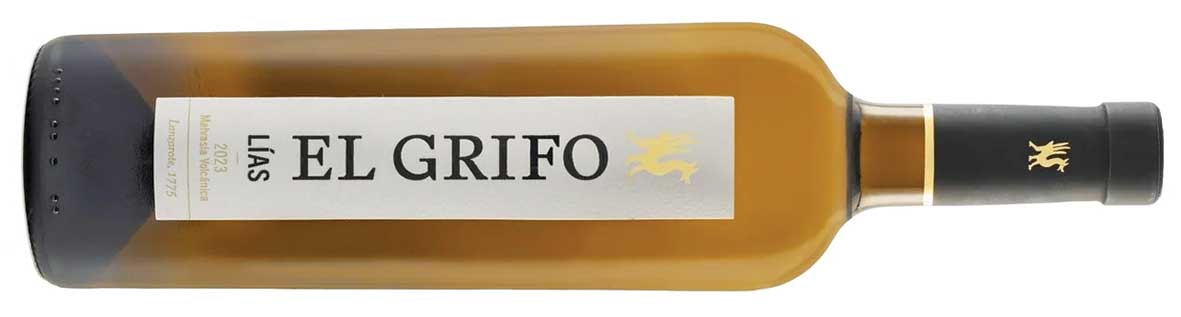

What’s 50 years to a producer celebrating its 250th anniversary this year? That’s the case for Lanzarote’s El Grifo – but I doubt that it’s ever produced a fresher and more delicious white wine than its 2023 Lías Malvasía Volcánica, with its blossom-and-apple scents and its tinglingly fresh, almost spritzy palate: more apple, more fresh flowers, then a slow slide towards salty breadth as the wine sits on your tongue. Unforgettable – and that’s before you’ve seen photos of the extraordinary black vineyards where the grapes grow.