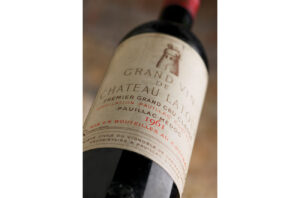

Take two growing seasons: 1961 and 2010. Take two red wines, the kind that most of us only get to dream about, from those vintages: Château Latour and Penfolds Grange. Compare. Latour 2010 (considered one of the greatest Médoc wines of the 21st century) contains 14.4% alcohol by volume (abv); Grange 2010 (5 stars and 99 points from The Vintage Journal) has 14.5%. Latour 1961 (lavished with perfect scores aplenty) has… 12.3%; Grange 1961 is at 12.7%. Grange ’62, regarded as a finer wine than the ’61, is even lower at just 12.2%.

Stranger still, written tasting notes suggest similarly styled wines. ‘Rich and voluminous,’ reads The Vintage Journal tasting note on the 12.2% Grange ’62, while Latour ’61 was (as noted by Robert Parker in June 2000) ‘Port-like, with an unctuous texture… full-bodied, voluptuous’. Michael Broadbent called it (in 1999) a ‘mammoth wine’. Rich and voluminous – at 12.2%! Voluptuous and mammoth – at 12.3%! Grange 2010, less surprisingly, is described as ‘a powerhouse’ (James Suckling, 100 points, 2014 note), while Latour 2010 is ‘a liquid skyscraper in the mouth’ (Robert Parker, 100 points, 2013 note).

That grinding gear-change in alcohol level, echoed universally around the wine world, is our subject. Alcohol levels in wine have risen significantly over the last half-century. Why has it happened, how do we feel about it and what are we doing about it?

The factors at play

There are many reasons why alcohol levels have risen so dramatically over recent decades. Anthropogenic climate change (the vineyard consequences of which include, compared to the 1960s, earlier bud break; hotter and shorter growing seasons, ripening under brighter sunlight and during longer day lengths; and earlier harvests) is the one we should take most seriously – since it affects not just wine production but our survival as a species. The largest contributor to global warming is atmospheric carbon dioxide: 317.64ppm in 1961 (according to mean measurements at Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii, begun in 1958); 428.55ppm on the day I write this.

There are, though, other wine-specific factors at play. Vine health has improved, meaning that vines perform more efficiently; soil management, pest control, canopy management and yield control optimise quality, which means that musts are richer; selected yeasts convert sugars to alcohol more thoroughly during fermentation.

Consumer preferences (in part based on critics’ scores) have also played a role, notably during the period (1990-2010) of Robert Parker’s critical prominence, when there was a shift towards late harvesting, giving ripe, opulent, powerful and often low-acid wines. Since 2010, the reverse trend has been underway in many regions, with wine-growers increasingly seeking qualities such as tightness, tautness and precision built around earlier harvesting and more prominent acidity levels, sometimes with lower alcohol levels.

Tamlyn Currin

The role of alcohol in wine

Author of Essential Winetasting Michael Schuster says that alcohol helps ‘fill and coat the mouth and lining of the palate with the fruit and flavours of the wine, and then supports and prolongs these sensations on the aftertaste… an affectionately embracing enabler, if you like’.

For Brian Croser, it ‘knits together all the other ingredients of wine’, while Argentine winemaker Alejandro Vigil of Bodega Catena Zapata calls it ‘the spinal column of a wine: flavour, aroma and taste hang on it and depend on it’.

Switching metaphors, taster Tamlyn Currin describes alcohol as ‘the ballast and hull of a wine – it is vital to balance, resilience, the centre of gravity, the “movement” of a wine’.

Wine creator Laura Catena stresses that ‘it’s at the core of what wine is’ – while Croser adds function to his definition: ‘It liberates the imagination, sharpens sensory perception and enhances appreciation of the totality that is wine. The turmoil in the world recedes during the contemplation of a good wine.’

Alejandro Vigil, Bodega Catena Zapata

As stated on the label…

How do we feel about the level of alcohol in our wines? How do we act and respond? Labels carry statements about the alcohol concentration, so you might assume that the issue is a simple one: if you want refreshment, choose wines with a lower alcohol level (13% and below, say); and if you like a richer wine, choose those with more (above 13%). Well, that’s a start.

There are, though, complications. The first one is labelling requirements. These vary by country. Wines (of more than 5.5%) imported to the UK have a tolerance of up to 1% abv each way, whereas in the EU, the tolerance is just 0.5% abv (sparkling and Australian wines excepted). In the US and Australia, the tolerance is 1.5% abv (reduced in the US to 1% for wines above 14% abv).

As duty in the UK now rises sequentially with the stated alcohol level, it would be wise to assume that most alcohol levels on wine labels in the UK undershoot by the permitted maximum tolerance. You might think that you have a 12.8% white in your glass; it could, however, be 13.8% in the UK, or as much as 14.3% in the US or Australia. Those are significant differences.

Or are they? The truth is that the stated alcohol on a label is a poor guide to the way that a wine tastes. ‘Freshness is, for me, a holy grail,’ says taster Tamlyn Currin. ‘But defining it is like trying to draw the wind. Sherry and Madeira can be two of the freshest categories of wines I know, and yet alcohol in these wines is between 15% and 20%. There are Amarone della Valpolicella wines that crackle with freshness at 16%. I have tasted wines at 12% that taste thin and stripped, and wines at 12% that taste outrageously generous. There are zero-alcohol wines that taste flabby.’

A bottle of wine, she goes on to say, ‘is an ecosystem within itself – a mini, liquid Gaia. Every part depends on every other part; every part is connected’. Focusing on alcohol alone is to lay a trap for your palate.

Bordeaux great Château Latour 1961 was bottled at 12.3% alcohol. Credit: Herbert Lehmann / Cephas

A question of balance?

Tasting expert Michael Schuster accepts the hazard inherent in alcohol perceptions: ‘Being precise about the effects of high alcohol in wine is about as easy as grasping quicksilver.’ But he maintains that there’s an objective element at play, too. ‘The old mantra that “the level of alcohol doesn’t matter so long as the wine is balanced” is akin to someone suggesting to a coffee drinker that it doesn’t matter if they’re served an espresso or an americano,’ he says. ‘The first is very strong; the second is much lighter. Both may be “well balanced”, but they drink very differently; not every coffee drinker likes both.’

Indeed. The point here is to understand your own palate’s relationship with ripeness. ‘What I find sufficiently ripe in a wine,’ says importer Doug Wregg of UK merchant Les Caves de Pyrene (which makes a speciality of wines at 12% or below), ‘another might find underripe. I love drinking energetic red wines that have red fruit character, that are sappy, verging on tartness, linear rather than expansive. These are wines on the point of ripeness, but a fraction under maturity. But I’m not a fan of dark-fruited wines that lean into “liqueur” flavour. That’s my palate.’

He might have added that this is where the post-Parker critical consensus is trending, as anyone studying the language of today’s wine critics will know. It’s also in harmony with the tastes of the natural-wine community, which Les Caves de Pyrene has long served. Doug is wholly on-zeitgeist.

‘The mass-market drinker often prefers the flavours in “riper” wines’ – Justin Howard-Sneyd MW

A range of preferences

There is, though, another point of view – that expressed by Justin Howard-Sneyd MW, an experienced former retailer and now a winemaker in Roussillon (as well as the DWWA Regional Chair for Languedoc-Roussillon). ‘I think the tendency for the wine-knowledgeable to criticise wines for high alcohol just because they’ve seen 15% written on the label is in large part just a fashion, used to virtue-signal and display knowledge,’ he says. ‘It may have become the norm among a small set of wine-expert commentators, and they may genuinely have developed this preference, but the mass- market drinker often prefers the flavours in “riper” wines. In blind-tasting tests with panels of experienced but “non-expert” wine drinkers, a distinct preference is shown for red wines with higher alcohol, body and often some residual sugar. With white wines, the preferences nowadays tend to be for crispness (Sauvignon from New Zealand), or soft neutralness (Pinot Grigio from Italy), rather than the fatness, butteriness and oakiness popular in the 1990s, and typified by Chardonnay. The rump of traditional Chardonnay enjoyers is still large, though, and they still mostly like – but are rarely offered – big Chardonnays.’

Personally, I love ripeness and soft, ample structure in wine; I don’t relish tart or linear wines. That’s my palate. And I’ve long thought too much attention is paid to alcohol because it’s stated on the label. Aroma, texture and balance are far more important; the label is mute about these. They are what convey drinkability and loveliness – and they may (as Tamlyn Currin suggests) be evident throughout the wine-alcohol spectrum, from 8.5% to 16%.

Doug Wregg, Les Caves de Pyrene

Mitigation techniques

Brian Croser

We live in a rapidly warming world. How are winemakers addressing the alcohol question, and where are we heading?

There are many strategies viticulturists and winemakers can adopt to harvest fruit with lower levels of potential alcohol than in the past. Minor changes include soil amelioration (cover crops and mulches, no till, regenerative hydrology, the use of biochar); increased vineyard shade (from agroforestry, trellising and canopy adjustments, and anti-hail screens); increased yields (the quantity of fruit produced by each vine); night picking, early picking and picking at multiple ripeness levels; and the use of wild yeasts and, for red wines, the use of stems in ferments. (Or, indeed, adding water to musts.)

Major changes include switching vineyards to north-facing orientations in the northern hemisphere and south-facing orientations in the southern hemisphere; planting at higher elevations than formerly; and changing the varietal mix or introducing field blends in a vineyard. ‘I’ve experimented widely with soil management, canopy management and viticultural orientations,’ says Louis Barruol of Château de Saint Cosme in Gigondas in the southern Rhône. ‘The main solution – what will really save us from making unbalanced wines – is to grow other varieties. We won’t give up Grenache overnight; it’s not going to happen. But what would help us massively is to use just 15% of Picpoul Noir and 5% of a very acidic grape to rebalance our wine. Grenache will still be at 80%; you’ll still have ripe Grenache expression. That way you can adjust to the climate evolution without shaking the tree like mad.’

All the growers I contacted made reference to (in veteran Australian wine craftsman Brian Croser’s words) ‘the well-established understanding that sugar and flavour/phenol ripeness are disconnected physiological processes’. The best wines, he explains, ‘are made when the two processes coincide because of the environmental (terroir) influence’. For Croser, as for most growers, the great challenge in global fine wine creation today is ‘to continue doing what each region has established as its best repertoire’ without these two ripening cycles unshackling, driving up alcohols and jeopardising balance.

Night harvesting in Moulin-à-Vent in Beaujolais. Night picking helps preserve freshness in the grapes. Credit: Jean Philippe Ksiazek / AFP via Getty Images

2003 heat: a grower’s story

‘When alcohol gets to a point where it generates unbalanced wines or a lack of freshness, then yes, there’s a problem,’ says Louis Barruol of Gigondas producer Château de Saint Cosme. ‘Wine is about pleasure and balance. You need to drink it. I don’t, though, know of a single example of a great wine made with green (that is, unripe) grapes, so the trend of earlier harvesting for lower alcohol and freshness is a simplification. Let me illustrate the difficulties. In the very hot 2003 vintage, I decided to pick late because, physiologically, the grapes were still unripe at 14.5%. It was shocking. I agonised, I waited, and I made wines that were almost 16% alcohol. They were ripe, because finally the rain came and the ripening really happened later. When I taste them today, I am kind of impressed by the way they evolved. But I don’t like them. They aren’t balanced; they don’t give me pleasure. They aren’t great Saint Cosme wines. We found the limit. But unripe Grenache at 13.5% or 14% wouldn’t work either. I’m sure about the extremes. Unripe grapes: no. Huge alcohol, unbalanced ripeness: no. In between is the answer. But it’s difficult.’

Louis Barruol. Credit: Louis Barruol

Embrace diversity

‘The point is to understand your own palate’s relationship with ripeness’ – Andrew Jefford. Credit: Nic Crilly-Hargrave Photography

Our climate will continue to warm over the coming decades; indeed the process seems likely to accelerate since the transition away from fossil fuel-based energy has, thus far, failed to lower atmospheric CO2 levels. Rising alcohols are the wine gauge of this process. Work in the world’s fine wine zones (notably Bordeaux) over the last decade shows that mitigation strategies such as those outlined above can check this rise; it’s not inexorable. Ongoing work on the genetics of both vines and yeasts may help further.

When and if those strategies fail, though, there are only two alternatives: a move to changed blends and varieties as outlined by Louis Barruol, or the search for new, cooler sites at higher latitudes or elevations. No one should assume these are necessarily happy outcomes – since great sites and their varietal partnerships are so rare.

My own hope, though, is that those who love wine will continue to treasure a range of alcohols in wine as they do every other aspect of wine’s expressive amplitude – and do so without the unhelpful aesthetic rigidity that can follow a focus on stated alcohol figures. Our wine reflects our world. Despite everything, both remain beautiful.

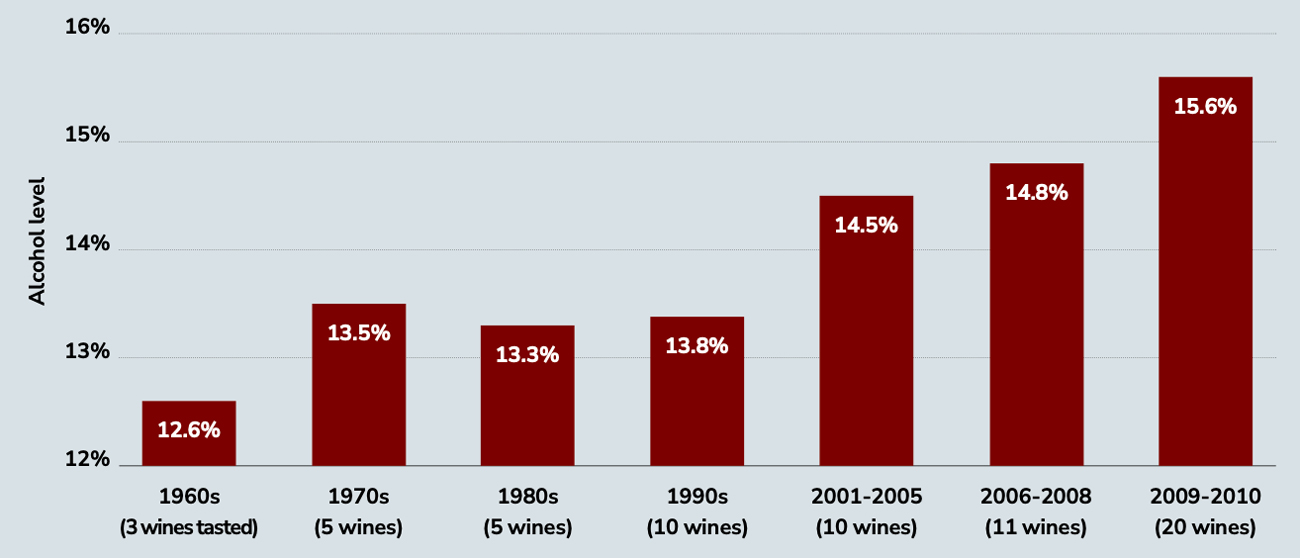

Alcohol changes in Napa, 1966-2010

In November 2012, a ‘Legends of Napa Valley’ tasting was held and reported on by one of the panellists, Alder Yarrow of wine blog Vinography, who cited the alcohol levels of almost all of the featured wines.

Averages of the stated levels in the Cabernets and proprietary blends are given below, along with the number of wines tasted.

One wine was criticised by Yarrow for overripeness and one for ‘some alcoholic heat’, but many more were praised by him, with the following comments made about wines of between 14.4% and 15.5%: ‘superb balance’, ‘remarkable weightlessness on the palate’, ‘incredibly balanced’, ‘I never would have guessed at its 15.2% alcohol’, ‘wonderful balance’, ‘seamless and balanced’.