Varietal thinking is treacherous… but it seems to be conceptually necessary for us. How else can we keep the worrisome chaos of the wine world at bay?

Once we start tasting, those familiar friends begin to swap clothes and identities, those landmarks turn up in the wrong places and those gateways open on strange, unexpected vistas. We taste, we drink, we relish. And then we ignore what we’ve just experienced. We go running back to our myths of varietal primacy and segregation – just so that we can keep our heads well organised.

All of this kept tickling me a little earlier this year during the Chenin Blanc International Celebration, held in early July in Angers and Tours, France. There was data aplenty. Fair enough: Chenin Blanc has a genetic definition, so its presence in the world’s winelands can be measured. South Africa has just over half of the world’s plantings (16,200ha in 2023) and France a little more than one third (10,700ha in 2023); the US, Argentina and Australia share the rest.

It’s South Africa’s most planted variety; in France, by contrast, it’s the 14th most planted, the fifth most planted white and the third most important variety in the Loire.

But here’s what matters. Any variety is a suite of possibilities, and those possibilities only take form and come into being when vines are planted in a particular site. It’s the site that will steer your wine experience – in coordination with the craftswoman or -man who shepherds vines through seasons and oversees the radical metamorphosis from grape juice to wine. Those efforts are vital. No efforts; no interest. As the talk and the tastings we shared made abundantly clear, the set of possibilities grouped under ‘Chenin’ can dazzle.

Almost the first word spoken about Chenin, by Anjou grower Patrick Baudouin, was ‘versatility’. ‘Plasticity’ soon followed (from the academics in attendance). South African vine-guardian Rosa Kruger (who cherishes the idea that old vines begin, after 35 years or so, to lose their clonal status and ‘change and reflect the landscape’) calls it ‘the chameleon variety’. Everyone stressed the community of possibilities that Chenin offers. For South African grower Chris Alheit, it’s ‘the very honest grape: it’s going to tell the truth about where it comes from’.

It has been in the Loire for the longest, so it’s no surprise that differences are most marked there. In Anjou it’s deep, sumptuous; in Savennières driving, masterful; in Saumur intense, bright and chiselled; in Chinon (and, soon, Bourgueil) firm, dry, upright; in Vouvray tender and intricate; in Jasnières slender, fragile, quenching.

Then… there’s time. Take it at different points of the season and it will give you a drench of differences, from bitter-hard and raw though springleaf, pear and apple via verbena, hawthorn and meadowsweet to a flush of yellow fruits and finally luscious autumnal extravagance. There’s a slower cellar clock, too. Ten, 20, 50 years pass and the wine deepens in hue and flavoury tone yet retains its sure-footed balance. No Chenin, just Chenins.

South Africa is still working its way towards all this. The scale and bone-structure of Chenin’s Cape expressions are very different from those of the Loire: larger and more chewy, broader in the beam, mingling honey, pollen, stone and softly tropical fruit notes.

What’s so encouraging, though, is that growers there are listening, waiting, asking questions, beginning sincere conversations with their sites, as you can now see from the gratifying range of balances in the wines, and their ever-quieter and ever-subtler weave of analogies.

No more statements or postures; farewell varietal confinement.

Few wines grown in the southern hemisphere have the same ease and spread of articulation, the same sense of unfussy belonging, as these do.

Unvarietal varieties, translators of origin, mothers of difference: of all this we need more.

In my glass this month

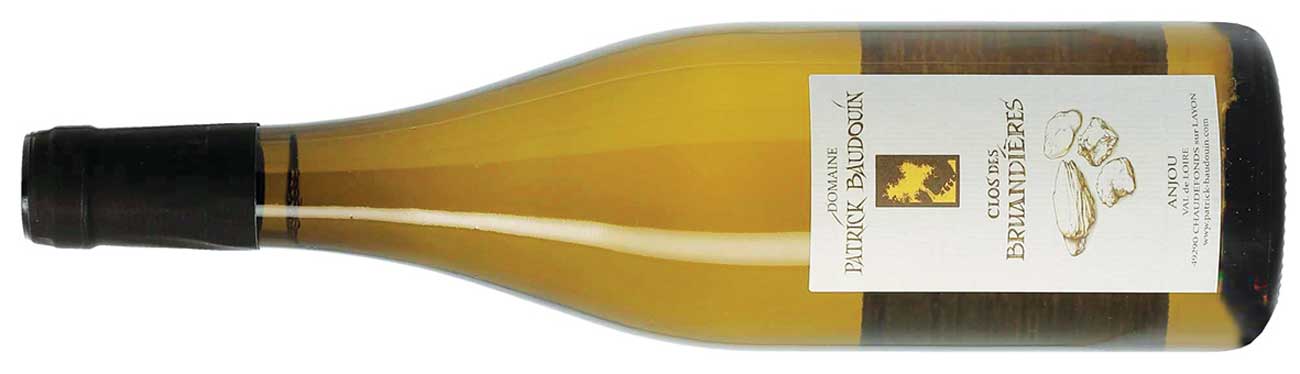

Hard to choose just one wine from all those I tasted, but here it is: thunderous and improbable, like an Anjou summer storm. Aromatically prodigious: a hayloft full to bursting, an orchard, a beehive. Rich, thick, vinous, mouthfilling, extravagant, burnished, glycerous and full… though not sweet; fissured, indeed, with acidity. This Pantagruel (a little Gargantua) is Patrick Baudouin’s Clos des Bruandières 2020 from Anjou: wonderful now, wonderful in a decade. Or two.